The value of a good scare

When I was a kid, I couldn’t stand horror movies. Even bad ones scared me to death, and, while some people enjoy that sensation, I did not. I couldn’t fathom what use these movies could have. I asked, “Who likes to be scared?”

But over the years, my feelings on the genre have matured. I doubt I’ll ever be a horror junkie, but horror movies do have value. They can be windows into the cultural psyche of a time period or a country, portals into people’s minds. They can be cries for help, protests, and cautionary tales. They feature the issues people care about, whether they know it or not. Horror movies are successful when they touch on something true; something truly frightening.

Right now, we’re in a period of social upheaval unlike anything the United States has seen since the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s, and it’s happening during a pandemic, which in turn is causing the worst economic crisis in decades. The latter two of those things are horrifying in themselves, and the first is the result of systemic racism, oppression, and police brutality, all of which are (say it with me) horrifying.

We live in some scary times. How will our horror movies reflect them?

Horror movies and themes in history

This isn’t an academic paper, and I hope readers will forgive me for some armchair film theory, but it’s important to at least address where I’m coming from. In the most basic terms, I’m working within a framework of film theory called cognitivism, popularized by film theorist David Bordwell. The idea is that films aren’t just entertainment, but are a source of understanding of people through the themes and semiotics and (depending on your source) psychology the movies use and espouse. When a movie’s thematic elements resonate with an audience, that resonance is reflected in the movie’s popularity.

When it comes to horror, my premise is simple: You can learn a lot about people by what scares them.

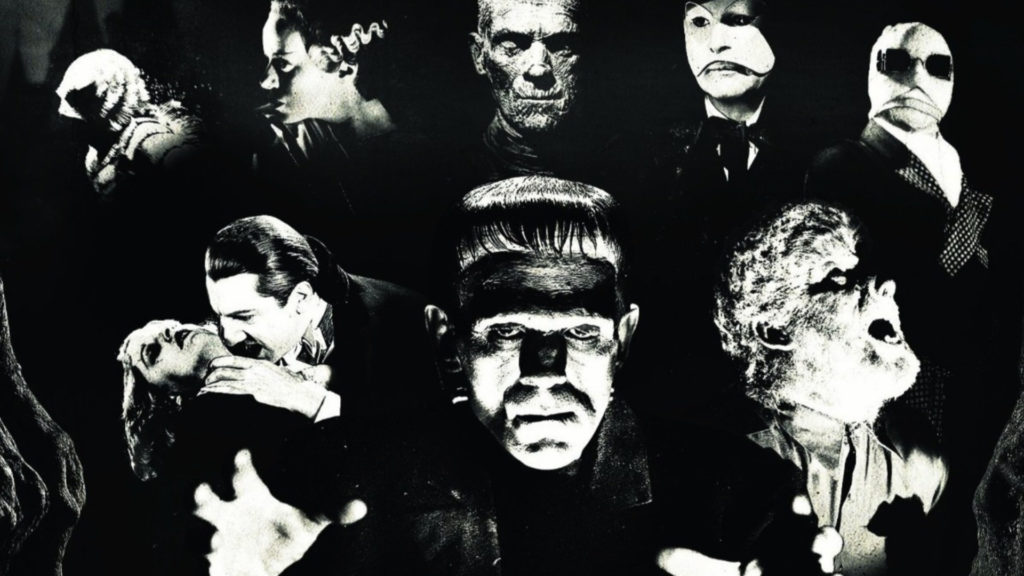

The 1950s

For example, in the 1950’s, people were particularly terrified of two things: 1) the Soviets, a foriegn nation bent on the destruction of the American Way; and 2) Nuclear destruction.

The first of these fears manifested in a popularity boom for the alien invasion genre with films like The Thing from Another World (1951), Invaders from Mars (1953), and The Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956). The reason the aliens resonate is because aliens are symbolic of the Soviets, a real world fear that people in the era held.

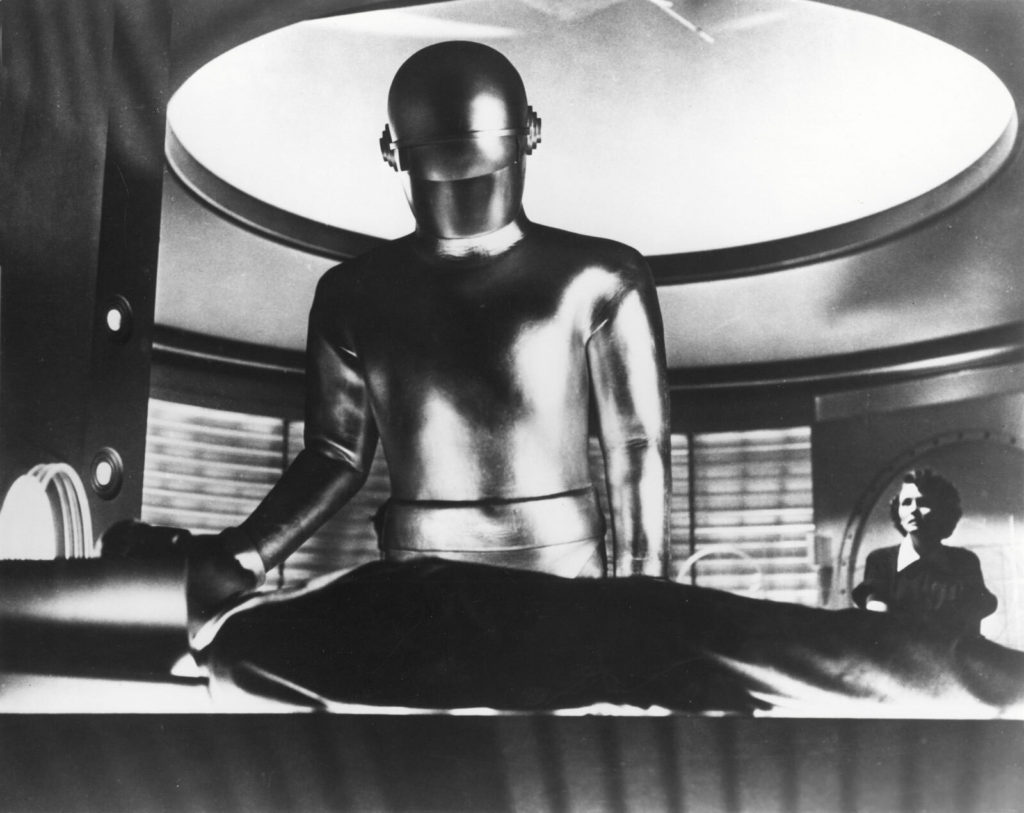

The second fear, nuclear annihilation, gave rise to movies like Them! (1954), and The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951), both of which spoke to fears about The Bomb. Them! features a threat created by nuclear radiation (giant ants), and speaks to the fear that science will, through its reckless pursuit of knowledge (bigger bombs), eventually cause our doom. The Day the Earth Stood Still, to be fair, isn’t really a horror movie. It’s a cautionary tale that calls for peace, lest the galactic community reject and destroy us with Gort–a chromed-up robot with a face laser–because we insist on nuclear armament. The threats in these movies are the result of our actions and have world-ending consequences. They’re symbolic of the threat nuclear war represented.

The 1960s through the present

Rosemary’s Baby (1968) used satanism and a demonic baby to relate the terror of domestic life and new motherhood for women in the 60s. From the late 70s through the 80s and 90s, a parade of slashers cut open the idyllic image of suburbia and/or punished teens for their sexuality. More recently, 2014’s The Babadook manifested depression, and Jordan Peele’s Get Out called out neo-liberal racism in 2017. The bottom line is, great horror has a long history of pointing a clammy finger at the scariest issues in society.

That’s not to say that things like mental illness and racism haven’t always been scary. But people accept them as frightening more now than ever before. In the past, white people, in particular, might have overlooked Get Out because the United States had elected a black president and racism was “over.”

However, in 2017, people heard the President refuse to publicly condemn the KKK, heard about the all-too-common deaths of Black Americans at the hands of police, and started to realize that maybe racism wasn’t as over as they’d thought.

Horror movies and themes in the future

We’re all trying to make sense of the world in which we’ve arrived in 2020, and I don’t have definitive answers. In this section, I’m going to hypothesize about themes I feel are likely to surface in the future, and dream a bit on loose ideas based on those themes.

I’m focusing on themes because they’re broader than specific symbols. As you can clearly see above, countless movies have similar themes, but the specifics are where the money is made. For instance, it’s easy to make movies about alien invasions, but only one writer created Gort.

If I could sit down and find perfect symbols to accompany the themes I explore below, I’d be off writing those screenplays! As it is, I’ll keep my ideas limited to loglines. If you like them, or if you have better ones, feel free to say so in the comments section!

Isolation/Crowding

These themes are both directly related to the pandemic. They’re opposites, but I think it’s important to acknowledge that both are legitimate fears brought about by (necessary) lockdowns. Being alone can be scary. Not being able to be alone can be equally so.

Is someone going to write a pandemic movie? No. Thousands of people have already written pandemic movies. But horror movies about a pandemic aren’t going to break through. The successful movies will conjure the way the pandemic made us feel: unable to reach those we love, unable to escape from a deadly, faceless enemy.

Example concept:

Subgenre: Sci-fi Horror

Logline: A scientist in an isolated research facility contracts an intelligent parasite and must extract it before it has a chance to spread to anyone else.

(The absence of) truth

Unreliable news is ubiquitous in our society. Those on the Right have their news sources, those on the Left have theirs, and the President just kind of…lies constantly, blatantly. The existence of facts seems to be increasingly up for debate, with people just choosing the narrative that works best for their pre-existing worldview.

It’s a profoundly disturbing phenomenon that is seeing some action in horror already. The recent remake of The Invisible Man is about gaslighting; a woman knows something is true, but the world tells her she’s wrong until she begins to lose her mind.

The idea that truth is subjective isn’t new. Akira Kurosawa’s famously explored this concept in his 1950 classic, Rashomon. I remember it anytime I read headlines on /r/politics on Reddit, which leave little doubt about the liberal bias of the posters. I’m not necessarily going there to get an objective presentation of facts.

And while Rashomon is a genius contemplation of bias clouding objective truth, it’s not really prepared for people like OAN’s Graham Ledger, who insists at the end of his “news” show on a “news” network, “Even when I’m wrong, I’m right.” If that’s not a terrifying viewpoint, I’m not sure what is.

Finding reliable and complete news is hard, regardless of your political stance. News suppliers have incredible power to skew things every which way. The idea that you can’t find the truth no matter where you look, is scary as hell.

Example concept:

Subgenre: Psychological horror

Logline: An author struggles to maintain her sanity as a film studio drastically alters her most famous work, insisting all the while that their adaptation is utterly faithful.

The (new) “other”

This might seem like cheating, but bear with me. For years, the Soviets were the “other” for Americans; this isn’t exactly a new trend. The Cold War brought forth movies that, at times, saw the “other” as monstrous and inhuman (The Blob, 1958), and, at times, saw the “other” insinuating itself into our lives and taking over, without anyone realizing until it was too late.

But today, the “other” isn’t from the Soviet Union; it’s from here, from the United States, and that’s way scarier. For some, the “other” emerges in the form of people refusing to open businesses, refusing to save the economy in the face of an overblown pandemic. For others, “the other” is a flat-earther, a mask refuser, a Trump voter. In either case, the “other” is unreachable, malevolent. They’re bent, consciously or not, on destruction.

While I think our current situation might be a bit closer to the Invasion of the Body Snatchers-esque quiet insinuation, it’s also different. In a sense, it would be easier to accept our reality if it could be explained away by a terrifying outside influence. But, we’re all Americans. The truth is, the new “other” isn’t an outside threat. It’s right here in America.

Case study: Get Out

In Get Out, the “other” we expect is the family of Rose (Allison Williams). We know we’re watching a horror movie, and they’re obviously up to something. They act friendly, but it’s clear they have no real comprehension of Chris’ (Daniel Kaluuya) life experience as a Black man. They’re on the outside, looking in, even before their plot is underway. They might as well be speaking another language. Russian, for example.

But where things get really scary is when Jim Hudson (Stephen Root) the blind man who previously showed some sympathy for Chris, reveals he’s involved in the plot, too. In the end, even Rose, Chris’ girlfriend, is complicit in the plot to destroy Chris. The true horror in Get Out is realizing that even those closest to Chris, who profess to understand him and speak his language, are against him.

Example concept:

Subgenre: Horror comedy

Logline: A pair of high school siblings battle against their own parents, who want them to attend their alma mater with the help of a secretive alumni association. The only catch? You’ve got to be a werewolf.

Unintended consequences

From systemic racism to the pandemic response, our institutions are failing frequently and spectacularly. They’ve been doing so for a long time, of course, but awareness is at an all time high. Still, the police exist (in theory) to protect people. The government exists (in theory) to serve the people. But legislators haven’t flawlessly established these systems, and they don’t perform their functions well at all.

Still, in essence, our predecessors built our institutions with the intent of doing good (just not for everyone). Similarly, either through their behavior, or the media they create or share, individuals can cause harm without intending it. Doing good takes more work than intending to do good.

What does this have to do with horror movies? Well, the idea that one can mean the best and still make everything worse, still hurt those they love or even complete strangers, is pretty damn scary.

Example concept:

Subgenre: Slasher

Logline: A couple of jaded, down-on-his-luck foster parents exploit their charges for money, but must run for their lives when a former foster finds out and seeks revenge.

The value of a good scare (revisited)

When I started writing this blog, I didn’t intend it to be bleak or depressing. It was just a thought exercise. But the truth is that exploring real fears isn’t easy. People aren’t truly afraid of things that don’t matter. Anyone can make a creepy-looking monster, but a monster isn’t a meaningful symbol on its own. It’s what that monster does; what it represents, that makes it really scary.

So why do people watch horror movies, again?

Because they’re a “safe” way to explore the dark parts of the human experience. They target flaws and offer catharsis either through the vanquishing of evil, or through evil claiming the victims who were too flawed to overcome it.

When we see something that truly scares us, we have an opportunity to figure out why. Horror movies don’t always have happy endings, but they do often show us how we don’t want to be.

So when you see a horror movie in the future about isolation, remember to be welcoming. When one is about crowding, remember that sometimes people need space. When you’re afraid that truth is gone, seek facts. When you’re afraid of the “other,” remember to have empathy. And when you’re afraid your ignorant actions will make everything worse, get educated.

Then go watch The Day the Earth Stood Still and enjoy how silly Gort looks.

Klaatu barada nikto.