Animation is amazing! It is older than film, has been on the forefront of cutting-edge technology since it began, and can tell stories and create visuals that are impossible in live-action. However, it suffers, at least in most countries, from a stigma – cartoons are for kids. Well, I beg to differ! Animation crosses all demographics, and people who dismiss animation as “kid’s stuff” are missing out on a spectacular medium which can inspire you and leave you awestruck. I would like to give you a hint at what goes into making an animation, in hopes you will learn to appreciate it for what it really is. This is going to be a long one…

I’m an animator. It’s my job title. My business card says “Animator” right on it, but that doesn’t just mean I sit there all day drawing pictures or moving characters in a computer or posing a puppet. I have to wear many hats and do many things, especially as a generalist animator. By generalist, I simply mean an artist that knows a little about a lot of stuff related to animation. A good generalist will be able to create an entire animated production from beginning to end, although the final result may not be as refined as it could be. That is where specialists come in. Which I am also. I am a generalist which specializes in texturing and lighting. However, as a generalist, please allow me to walk you briefly through what it takes to make a full CG animator film, such as Zootopia or Storks. And remember each of these jobs has a specialist behind it as well.

Today, most animated films are “CG” (Computer Generated), so I will focus on what a CG film involves, but traditional (or

“hand-drawn”) animation has many of these same steps and some unique ones of its own. Many of these steps happen all at once or in different orders, and some productions have more roles and other have less.

The concept begins with a script and storyboarding. Storyboarding, in short, is drawing rough sketches of what each scene should look like. This way you can change a camera angle, rewrite a line, add or cut scenes, and more, all without spending a lot of time and money. Unlike live-action storyboarding, animation storyboards are far more detailed and have to include every action the character and camera makes. This storyboard is usually turned into something called an “Animatic,” which is just a timed-out version of the same thing with rough voices, to get a feel for the flow and length of the film. It is continuously edited and updated throughout the entire production.

While the storyboard is being worked on, a team of designers are busy creating the look of each character, the world they inhabit, props they use, and environments they live and work in. Building a character’s look is a long and arduous process that takes hundreds of iterations and endless amounts of refinement. A lead artist will guide the team and work with the director to make sure everything is exactly as they envision it. Often the team will even look at the voice actor selected for inspiration on the look of the character as well.

Speaking of voice acting, early on in the process voice actors are brought in to give a voice and life to the characters. Sometimes, the actors will even ad lib lines, which sometimes makes it into the film and can redefine the personality of the character. Their performances are often recorded on video too so animators can use their expressions and personal quirks in the character’s performance. Ever notice how Belle from Beauty and the Beast regularly brushes hair out of her face, that’s because her voice actress, Paige O’Hara, would do the same thing in the recording booth.

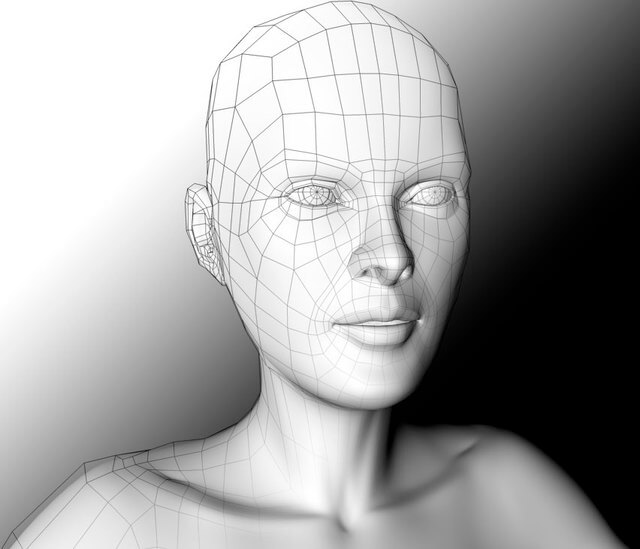

In CG films, you need to build the characters in 3D software. That means modeling. Modeling is a challenging

profession, but the best modellers can make absolutely amazing works of art. When modeling characters for a film, they have to make sure they match the look and style of the character, as well as follow proper form (called “Topology”) so they can be animated without wierd errors. But characters aren’t the only things that need to get modeled. Everything does. Every background character, every article of clothing (an entire profession by itself), every prop, every environment, every bug, animal, piece of trash, blade of grass, and so on. Many of these can be done with the aid of smart computer programs that allow you to build a forest, for example, with a simple click of a button, but someone had to program that tool.

Programmers are probably not something you’d think are needed in a CG film, but they are imperative. Most companies have a team of programmers and script writers that can make tools for the artists to use to do things they wouldn’t be able to do otherwise. Those amazing outdoor scenes from The Good Dinosaur were made with the help of software that allows the artists to populate a hillside with trees, each covered with leaves and details, and each with unique traits. It takes a lot of smart programming to make this happen, and no it isn’t cheating. It is working smarter, not harder. So, if you ever think a computer just does the work for the artist, it simply isn’t true, and someone had to program that software as well.

Once we have everything modeled, we can move on to the next issue, the models can’t move! Just because you modeled it to move doesn’t mean it can yet. To do this, you need a Rigger. Picture it like this, if you want to make a puppet, like the characters in Kubo and the Two Strings, you have to build two parts, the outside of the character that makes it look like right, and the inside skeleton (called an “armature”) that allows that puppet to be posed and moved. For a digital CG character, you need to build a digital armature, and these can be complicated. Every single thing that moves either has to be rigged to move or programmed with “dynamics.” Imagine building a skeleton for a character, now imagine building the muscles as well, and controls to make it easy to move. Now add on more controls to move props, hair, clothes, and more. And just building the armatures isn’t enough, you also need to tell the skin how to react to those movements, which is why proper topology is so important. You literally have to paint the effectiveness of each joint of their skeleton onto the skin. It is a technical and difficult job that requires a lot of knowledge of the software and math.

Dynamic elements also have to be built and applied. Skirts, hair, grass, anything that would be easier to allow a physics simulator to animate has to be programmed and tweaked. How heavy is it? Does it have a curl or bounce to it? Does it float? How much friction does it have? Someone figures all this out so the artist can get realistic movement from it.

And we haven’t even gotten to painting the characters yet, something called “texturing.” A team of texture artists have to paint every single character and prop and environment. This doesn’t just mean the colors you see, but also the way the light interacts with the surface, “bump maps” which allow more refined details on the character than the modeller can put in, and even complicated effects like subsurface scattering. Why does a ring look shiny and not dull like a shirt? Someone textured in the metallic properties. Why does a character’s ears glow red when a light is behind her? An artist painted in subsurface scattering to her skin. This is a very complicated and technical job, which involves a lot of knowledge of the way the computer processes these images, while still requiring a high degree of artistic talent.

So now we have a script and our world and characters are built, can move, and look good; time to animate, right? Wrong. References. You need animation references. Character animators will come in and study performances of the voice actors, hire body actors, and record their own performances of every second a character is on screen. Once that is done, the animators can start to animate the characters. That includes anything that isn’t dynamic, and some things that are. There are even technical animators that will animate mechanical or background elements, things that don’t require a character performance, such as a car. The character animators are the rockstars of the animation world, because they are the ones that provide the acting performance to the characters, but a whole team of people support them and build the tools they use.

The camera also needs to be animated and set up. Digital cameras have digital lenses and a cinematographer has to come in and make sure the cameras are properly set up. Meanwhile, the film is being animated scene-by-scene, shot-by-shot, and the animatic is updated, edits are made, and animated scenes replace the old storyboarded scenes in the animatic. This “Work In Progress” (WIP) file eventually gets updated until it becomes the final film. But we aren’t there yet. We still haven’t lit anything.

Without lights, the animated world is pure black. A lighting artist has to illuminate the film. This doesn’t just mean adding some lights so you can see it. They also want to make it look natural and realistic while using the lights to “shape” the characters, drive the story, draw the eye, and add visual interest. This is another one of those technical and artistic roles that require math, a good eye, and a thorough understanding of the software and real-world lighting physics. Colors of the lights are very important and can make or break a scene. The same scene can be made to look and feel funny, scary, exciting, or anything else just based on how it is lit. A good lighting artist has to study films, animated and live-action, to learn techniques and styles. However, digital lights don’t behave like real lights do, meaning they can do unnatural things the artists need to understand. Not only does good lighting make a film look amazing and define the feel of the movie, but it can also make the film take longer to render.

What is a render? Simply put, all the data you told the computer to look at now has to be processed. Every texture, every polygon, every dynamic strand of hair, every reflection of light, every camera lens distortion. They all have to be processed in high quality to get the final look for the film. The artists see a representation of what they are doing before it is rendered, but it is simplified and rough, so you need to fully render it out to make it look right. Now that the lights are added, the computer has to calculate how bright every single one of these elements is, what color the lights are and how that affects the surface, the decay of a light, the shadows and their qualities. There are literally thousands of calculations for every single pixel of every single frame that the computer has to figure out. There are tricks to make this render faster, and of course better programming and faster computers are important too. Sometimes a single frame of a film can take two days to render on a supercomputer. And yes, there are people whose job it is to make sure the renders don’t fail, and make them render faster, the Render Wrangler.

Finally, the film is finished, right? Not yet. You still need to do all the visual effects, which can be done before or after the animation renders. Not to mention the editing, the color grading, the foley, the sound mixing, the music, stereoscopy, and everything else a live action film needs. It is only after all this is done, and sometimes more, that you can call the film complete. A generalist animator needs to know a little about all of this stuff. I can storyboard, model, rig, animate, texture, light, render, add visual effects, edit, and color grade a film. I’m not a specialist in all of these, but that is what makes being a generalist so much fun. I have my hands on every part of the filmmaking process. Granted, specialists are needed for big budget films, which is why I have a specialty as well.

I know this was a lot. There is so much to talk about in the animation process, so many things that have to be done even on small-scale projects. Perhaps this brief overview has helped you earn a new appreciation for how complicated and difficult it is to make an animated film. Maybe you will see the artistry behind the typically kid-friendly medium, and learn to explore the more mature and adult sides of animation. I just hope you don’t dismiss animation as some kid’s cartoon. It took a team of talented passionate adults to make it, and it is worthy of appreciation.